Coonskin: An Uncensored Portrayal of America

Coonskin; the incredibly controversial 1975 animated film shunned for its use of animated racial stereotypes and insensitive name. Originally to be named Harlem Nights by its creator, Ralph Bakshi, it was renamed a second time for the censored version, Street Fight. But what was this movie really about? Was it simply a racially charged precursor to Roger Rabbit, or is there a deeper meaning laid behind the offensiveness of its animation?

To begin, I’d like to state that researching and conversing on this movie has been rather painstaking. As a white individual, speaking on this movie is like walking on eggshells, especially when the name begins with a slur. Despite this however, I believe this movie is too important to pass over. Due to my own personal convictions, as well as for the sake of the viewers of this content, any racial terms used classically to belittle people of color will be censored in this essay.

The film follows two narratives of three black brothers, recited by a live action cast of the same nature as the animated characters- Brother Rabbit, Bear, and Reverend Fox. Hustlers at heart, the three flee their hometown to find money in Harlem, “home to every black man.” The film begins with an animated scene- two black pedestrians (drawn with vaguely simian features throughout the production) appear on screen, simply beginning the movie with the phrase “F**k you” as a shock factor. “Alright, I’m gonna give you a little bit of example,” the one on the left says: “I heard that three hundred and fifty of you white folks committed suicide by jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. And out of the three hundred and fifty, there was only two that was [n-word]– and one of them was pushed.” After this frightening statistic, the two cackle together as they walk off camera, leading the movie into its intro credits- Scatman Crothers’ Ah’m a [n-word] man.

Within two minutes of the movie’s runtime, we can already see the blatant racist stereotypes put in place by white hollywood- large red lips, loud slurred english, the use of the n-word, and the Jim Crow stereotype. It only took two minutes for most ticket holders to cry out in disgust and take to the streets in protest of the showing of the film. However, the NAACP saw what the naked eye could not. These stereotypical characteristics weren’t placed in derogatively, they were shown to make one thing clear- this is America. This film is by no means subtle, however, this seemed to fly by many viewers’ heads. The exaggerated aspects of the black characters were meant to hold a mirror to the white movie-goers stating “this is your view of the African American population.” Street Fight was the original This is America in movie format.

The film digs deep into the history of animated atrocities of race and shines a light on it. Animated almost entirely by a black studio, Street Fight threw the spotlight onto some of the first African-American animators. What many don’t know however, is the film’s nod to Disney’s famously racist Song of the South. The cast of characters featuring a black narrator, a rabbit, bear, and fox all point to being a spoof of Disney’s fatal usage of the classically African American story of Br’er Rabbit, going so far as to using its ending as the movie’s climax. As a parody of white animation’s use of black stereotypes, Ralph Bakshi decided to use this cast of characters to satirize white America’s portrayal of black characteristics, not to encourage it.

To finally start the movie, “Preacherman,” the human persona of Reverend Fox and Sampson, the personified version of brother Bear drive to the Oklahoma state Penitentiary to bust out their buddy Randy behind bars in the live action scenes. This humanoid Brother Rabbit sneaks outside the compound at night accompanied by an elderly inmate. Stating that he knew a group just like the characters in the jailbreak, he busts into the story of Rabbit, Bear, and Fox; and how they took over underground Harlem.

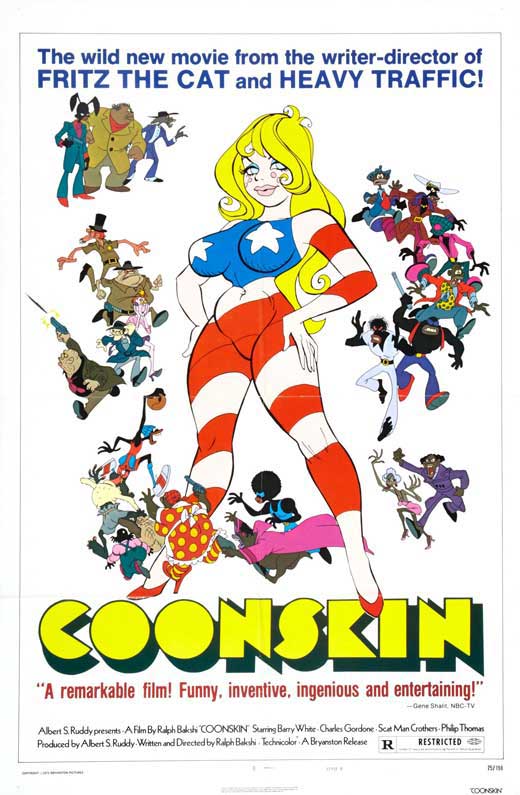

While this film was an animated feature, none of the stories or plot depicted is entirely fiction. The film truly is a woven basket of oral traditions, revamped into an adult world, spinning tales from real events. During the production of the film, Ralph traveled to harlem in order to hear black stories, leading to the appearances of “Malcolm the Cockroach” the story of a single mother spurned by the sadness of poverty, “Old Man Bones” the experience of a destitute black man experiencing the ill-effects of the Trickle Down Economy, and “Miss America-” a collection of scenes depicting a voluptuous white American persona and her violent interactions with different people of color with differing ideologies. Murdering and mutilating almost all black characters she comes into contact with, America lures her prey in with the promise of equality and freedom, only to brutally destroy their dreams and their bodies. This, of course, is one of the most obvious statements of distaste for America’s treatment of its black citizens.

This film does more than satirize white culture however, it also has critiques of black culture as well. Fueled by real stories of the seedy streets of the seventies, the fictional “Savior’s Simple Revolution” is used as a plot device to converse about the futile attempts of racial supremacy led revolutions. Critiquing the many violent uprisings attempted in the 1970’s in order to achieve black supremacy, Savior and his men are easily overthrown by smooth-talking Brother Rabbit, and quickly turned into a cartel (as most failed revolutions did). Similar to Boondocks, while there is something to say about toxic white culture in the film, there’s also a piece dedicated to the toxicity of certain black ideologies developed over time.

After meeting with Savior’s posse, Rabbit is forced to prove himself as leader in this newfound gang. To earn reputation and status his job is to kill the Harlem cop Mannigan, a corrupt officer running the New York mafia’s rackets. An incredibly prejudiced man, he is known for not bathing when expecting black company, since they “aren’t worth washing for” After luring Mannigan out by robbing each brothel, bar and gambling rings under his jurisdiction, Rabbit drugs and kills him with relative ease, leaving the godfather and his minions as the next target. After the mafia’s failed attempt at Rabbit and Bear’s life, Bear goes to find Fox for some solitude away from the drug racket uptown, only to find the preacher now runs a “legal-like” cathouse downtown. After a night at his bordello, Bear is convinced by Fox (currently working as a double agent with the mafia) to take up boxing. Quickly becoming the heavyweight champion, it becomes clear that the only way a black man can be accepted by the scantily clad Miss America is to be a source of entertainment for whites, after she is depicted ushering in white fans, screaming for blood in the ring, and celebrating Bear’s continuous success (and more importantly, his money).

After this, Miss America interacts with Brother Rabbit and his gang at a bar, telling him about Brother Bear’s championship status. Holding him in her clutches, she coerces him into setting up a title fight between Bear and one of Rabbit’s fighters. Plotted from the beginning, Preacher Fox tips off the Godfather, explaining to him that his chance to kill Brother Rabbit is nigh. However, unbeknownst to the mafia, Rabbit (working with Fox) sets up a “Tar Baby” wearing his outfit in the stands.

While the term is disputed on whether it holds racist connotations, the phrase originally comes from the tale of Br’er Rabbit. After repeatedly stabbing the dummy, the mafioso’s all become stuck in the duplicate’s sticky tar- Brother Rabbit sarcastically hops by, mimicking the animation used in Disney’s Song of the South adaptation, and recites Br’er Rabbit’s lines from the story: “Hey! Hi there!” Stopping in his tracks with no response from the indisposed tar covered godfather, he backtracks; “What’s the matter with you? You’re not hard of hearing. Look- if you don’t say hello by the time I count two, I’m gonna bust you.” In an attempt to bash Disney’s self-destructively racist acts, this scene plays out almost exactly the same way as in the 1946 film. After lighting the fuse to comically cartoonish dynamite and setting it at the Godfather’s feet, the trio flee jeering that “It was a tar rabbit, baby!” ending the movie with the three brothers driving away as the kings of Harlem. As for the Jailbreak? Randy and the gang ride off into freedom with the narrator in a bullet ridden car.

Street Fight is by no means perfect. However, the lack of change from the events of the 1970’s to the present show’s how important of a film it actually is. We all have something to learn from this film- truly an eye-opener of how truly little we’ve evolved in racial equality from nearly half a century ago. Where people see this politically incorrect film, I see a work of art, begging to be understood- neglected by its original audience, this film needs to be seen by the youth of today as a lesson of continued American injustice.