Adapting “Frankenstein” Through the 19th and 20th Centuries

When asked to describe Frankenstein, most people will give you an image of a bright green blockheaded, mindless monster with stitches across the forehead and bolts in the neck that walks with the speed of molasses; allowing his victims time to run away, and killing those who don’t run fast enough by ripping out their hearts. However, Mary Shelley’s version of Frankenstein is incredibly different. In Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein is a scientist who maps out his own fall and wishes to play God by creating his own species, thus creating the Wretch. The image of the Wretch, Victor Frankenstein’s creation in Mary Shelley’s novel, has changed drastically through the 19th and 20th centuries as his character was blended with contemporary fears and hysteria to remain a relevant monster. The major changes between Mary Shelley’s 1818 Wretch and the Wretch from the late 20th century are changes to his skin tone, intelligence, morality, and the adoption of the name Frankenstein in place of the Wretch. These characteristics of the modern day Frankenstein were influenced by social views and hysteria, especially by views of race, slavery, and the Other, polio and ableism, and the roles of women and what makes a monster.

Mary Shelley first wrote and published her novel Frankenstein following the declaration of a ghost story competition posed by Lord Byron. 13 years after the first anonymous publication of her three-novel-long Frankenstein, Shelley published the 1831 edition, which is now the more well known of the two. In her author note of her 1831 edition, Shelley claims “I have changed no portion of the story…I have mended the language where it was so bald as to interfere with the interest of the narrative…leaving the core and substance of it untouched” yet the characters and motives change drastically between the 1818 edition and the 1831 edition (Shelley, 1831). In the 1818 edition, Shelley places Victor Frankenstein in a parental position over his creation. Conflict arises when Victor Frankenstein abandons the Wretch alone after his “birth” due to Frankenstein’s disgust and abhorrence of his creation. In this edition, the plot and conflict circulates around Frankenstein abandoning his progenial son, who then must teach himself morality, and the blame and focus in on Frankenstein for his mistakes and abandonment of the Wretch. This was likely influenced by Mary Shelley losing her own child around the time she began writing Frankenstein. Meanwhile, in the 1831 edition, Victor Frankenstein is removed from a parental role and instead likened other gothic novel heroes who consider themselves superior to all others and attempt to “play God” with their actions to prove their superiority. The removal of a parental obligation to care for and teach one’s offspring distances Victor Frankenstein and the Wretch much more; there’s no longer an obligation and assumption for one to be cared for, thus making Victor’s hatred and avoidance much more excusable and less pivotal, and the focus begins to shift to the actions of the Wretch. Shelley’s description of the Wretch is intended to be all encompassing and builds vaguely, though perhaps not purposefully, off of slave archetypes in his stature and violence, and is intentionally left nameless to enhance how the all-encompassing horrid and grotesque is impossible to name, and to purposefully distance him from anyone and anything. By limiting the Wretch by making him nameless, and only addressed by titles of contempt like daemon, creature, ogre, devil and the other countless names used by Victor to refer to his creation, any identity or sense of belonging for the Wretch is taken away (Duyfhuizen). Despite how some productions, like Leigh Hunt’s 1823 stage production of Frankenstein, where Wretch in the playbill was written as “____ By Mr. T. Cook,” kept this “Nameless mode of naming the un[n]ameable,” the ability to remain unnamed held by the Wretch fades as more time and adaptations come to pass (Shelley).

In Shelley’s novel, the Wretch is described as above human, with supernatural speed and strength that Victor lacks. The Wretch is also much taller, enough to loom over all others (Shelley). Victor declares that if only the Wretch wasn’t so physically conventionally hideous, he would be easily heralded as something divine, and despises his creation in part for not being perfect and superior in appearance, and an object to show Victor’s own superiority. In the 1831 edition, The Wretch begins to reflect contemporary views of the Other, a racially motivated character to separate “Us” from “Them” that was particularly prevalent in colonial times. In this version, the Wretch is very clearly feared and hated for his appearance; markedly different and more horrible than that of people, and is thus isolated and attacked by people who see him, to the point that he sees demanding Victor to play God again to create a wife as the only way to not be alone, to not be stuck in the role of the Other.

As Frankenstein grew in popularity, artists of early artwork struggled in how to represent the Wretch. In very early artwork, the Wretch played more off images of Michelangelo, and was drawn to look like or even better than humans, but as time went on artists began to draw on the racial stereotypes, particularly those of Jamaican slaves that were already present in Shelley’s descriptions of the Wretch. In his strength, hair, and countenance, popular images associated the Wretch with representations of people of color, and began to solidify the Wretch as the Other (Malchow).

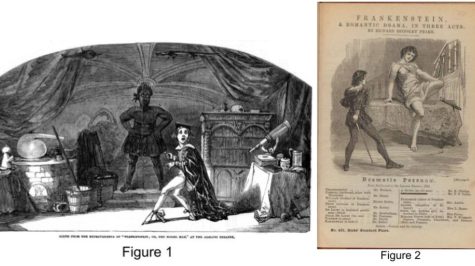

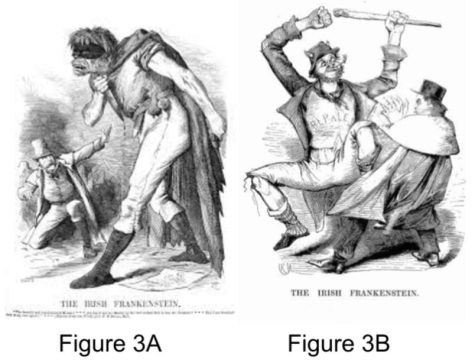

Artwork of the Wretch (now starting to be called Frankenstein for convenience and to solidify into a character) now veered heavily into racial caricatures, something frequently present in newspaper art of Frankenstein; or, The Model Man as plays of Frankenstein continued to appear in theatres (Figure 1). Portrayals like the brochure for Frankenstein; or, The Model Man continued to be made and became mainstream, despite how the earlier and first depiction of the Wretch, like in Figure 2, portrayed the Wretch as more of a character like Michelangelo; as an ideal being. As more time passed the character of Frankenstein began to leave that Michelangelo-centered image to fully embrace the racial caricature used to place the Wretch as Other. In art that continued the theme of race, the Wretch appeared with a stature and appearance that built almost entirely off of racial stereotypes, something that’s visible in the darkened skin, unruly hair, wide lips, and larger forehead that were almost always present, and later transformed into the blocky head of today’s Frankenstein. As Frankenstein was adapted into stage productions, this racial black archetype was enhanced even more as actors of the Wretch would oftentimes don blackface for performances and from early performances in the 1820s to the 1880s, and would act either similar to Southern slaves with constant singing or dancing while on stage, or like Caliban slaves; mute and only tamed with the usage of music (Malchow, 121). This caricature of the Wretch continued to imbed itself in society, as Frankenstein’s creature became a common role in minstrel shows and spread even more into the role as the Other, and the subtleties of Shelley’s work were lost in over exaggerated and simplified performances. (Malchow, 121).

Artwork of the Wretch (now starting to be called Frankenstein for convenience and to solidify into a character) now veered heavily into racial caricatures, something frequently present in newspaper art of Frankenstein; or, The Model Man as plays of Frankenstein continued to appear in theatres (Figure 1). Portrayals like the brochure for Frankenstein; or, The Model Man continued to be made and became mainstream, despite how the earlier and first depiction of the Wretch, like in Figure 2, portrayed the Wretch as more of a character like Michelangelo; as an ideal being. As more time passed the character of Frankenstein began to leave that Michelangelo-centered image to fully embrace the racial caricature used to place the Wretch as Other. In art that continued the theme of race, the Wretch appeared with a stature and appearance that built almost entirely off of racial stereotypes, something that’s visible in the darkened skin, unruly hair, wide lips, and larger forehead that were almost always present, and later transformed into the blocky head of today’s Frankenstein. As Frankenstein was adapted into stage productions, this racial black archetype was enhanced even more as actors of the Wretch would oftentimes don blackface for performances and from early performances in the 1820s to the 1880s, and would act either similar to Southern slaves with constant singing or dancing while on stage, or like Caliban slaves; mute and only tamed with the usage of music (Malchow, 121). This caricature of the Wretch continued to imbed itself in society, as Frankenstein’s creature became a common role in minstrel shows and spread even more into the role as the Other, and the subtleties of Shelley’s work were lost in over exaggerated and simplified performances. (Malchow, 121).

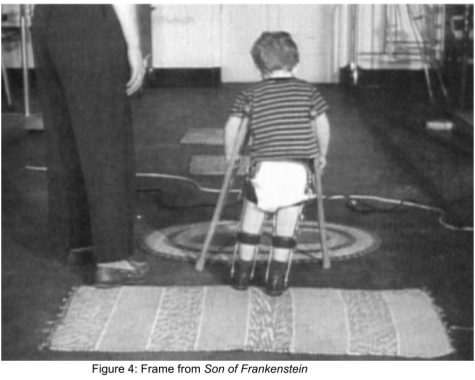

Following the earlier productions in 1823 and through the 19th century, Frankenstein became a common allegorical representation of the Other and became used for propaganda in forms like the Irish Frankenstein (Morgan). The Irish Frankenstein was an anti-Irish independence character used in Punch Magazine to comment on O’Connell in the 1840’s (Figure 3A), the Fenians in the 1860’s (Morgan), and the Phoenix Park assassinations in 1882 (Figure 3B). Later, as Frankenstein was adapted to film, these racist characteristics continued over into film, particularly in the build and countenance of Frankenstein, his ability to speak and subservient or violent behaviour.

Whale’s Frankenstein, published in 1931 under Universal and the first of a series with Karloff playing Frankenstein’s creature, solidified most of what the character Frankenstein stands for today, hand-in-hand with the association of Boris Karloff as the Wretch. Before Whale’s production, the skin tone of Frankenstein’s creature frequently changed in dark green, yellow, and blue hues and even corpse-like white, with the main intention being to portray him as Other (Malchow). Because of the limitations of film at that time; with panchromatic film just starting to be developed, allowing a larger realm of shades of gray that could be attained through brighter colors like in the Addams Family, the actors of the Wretch were most often, if not always, caked with makeup and face paint to appear distinctly Other while on film (Walker). While Whale’s Frankenstein was no different in using excess amounts of face paint on the actors, it solidified Frankenstein’s skin color in people’s minds, mostly due to how Karloff as the Wretch set the precedent for what Frankenstein, as the creature, should appear as. Karloff was the first actor to play a well known, but not seen on the screen, character of a monster. The character appearance of Karloff as the Wretch became prominent in society, with interviews from him describing the process and countless newspaper ads centering on him in the role of Frankenstein (Canfield). As Frankenstein continued to play in theatres and gain attention, Karloff was played as the Wretch in the following Universal films, cementing his epochal role as the “original” Frankenstein and the reference for those later to come, so much so that Karloff’s creature became a specific term to reference this precedential portrayal of Frankenstein. Whale’s Frankenstein was pivotal in both how it shaped the current-day view of Frankenstein and how the movie incorporated social hysteria into the character of Frankenstein’s creature.

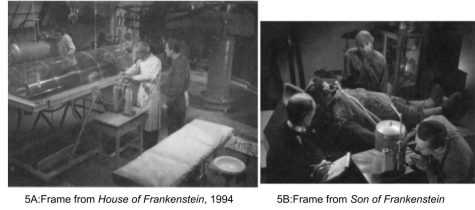

Karloff’s creature; with green-grey skin, a protruding ape-like forehead; likely inspired by the racially motivated character of the stage, bolts in the neck and a slow, shuffling gait shaped the contemporary image of Frankenstein (Codr). This singular image, found on book covers, paltry Halloween decorations and the minds of people is that of Karloff’s monster(Figure 4). However, this image is quite different from that which Shelley gives and while the skin tone shift may have been necessary for film, the choice to take the speed and agility of Shelley’s character and replace her Wretch with a slow, shuffling, and stiff monster was certainly intentional and played off of social hysteria, specifically that of polio. As is common in most horror movies, Whale’s Frankenstein is intended to incorporate and reflect social fears, and the main fear the public held at that time was that of polio. In 1916, though there were certainly earlier outbreaks, polio took the western world by storm with 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths in the U.S and 8,900 cases and 2,400 deaths; 80% of which were children under 5 in New York alone(Yale). Most movies before Frankenstein that included polio were melodramatic sob stories, with a focus on the inevitability of peoples’ bodies failing them as people contracted polio. However Frankenstein and concurrent horror movies began to show polio and the unethical medical experimentation done by doctors on polio patients as something a bit more monstrous and inhuman.

Frankenstein, as a character, began to draw extreme parallels to people with, and dying of polio (Codr). His shuffling gait, stiff muscles, lack of control over facial musculature, abnormal and staggered respiration, locked muscles and physical deformities, are all traits shared with those with polio. Even survivors of polio began to see themselves reflected in the character of Frankenstein, with Charles Mee, a playwright with spinal polio, explaining how “[they] sat me up on a cot and swung my steel-clad leg over the side. Like Frankenstein…. Then they tilted me forward and lifted me up at the waist on my left side only so that the foot came off the floor, and my steel leg swung forward absurdly.” and other survivors like Perrault bringing up how even if survivors were able to move again after being paralyzed, it was only with “Frankenstein-like movements.” And even after better medicinal care was found and social fear died down a little, polio continued to stay integrated into Frankenstein’s character in the minds of the public.

Shelley’s creature and film adaptations of Frankenstein were also distinctly different in the intelligence and comprehension skills of the Wretch, as polio connections continued to drastically shape the Wretch. Universal’s Frankenstein series continues to employ Karloff to play the Wretch, yet between the movies, his character would switch between being able to talk and being mute, and even on acting much more occasion subservient to a supposed “master”, something also influenced by the struggle between balancing the slave archetype in his character and the polio representation. As the series continues, Universal strengthened the polio references, giving a child the same gait and breathing patterns (Figure 4), and later giving Frankenstein’s creature a full breathing apparatus and iron lung (Figure 5A, Figure 5B). Whale’s movie also sets a number of the common scenes used and known today, such as Caroline running away along the edge of a lake, and Victor monologuing in the family crypt (Whale). The Universal films; like Whale’s, focused more on religious symbols, portraying social hysteria, and the more unwilling medical side of Frankenstein’s creature in his actions, all things influenced by social perspectives and events at that time (Picart, 24). While in contrast, Hammer Film Industries begins their Frankenstein franchise in 1957 with The Curse of Frankenstein and focuses more heavily on the medical creation of Frankenstein; adding the common-place stitches in his face, on incorporating sexuality and sexual undertones to the characters, adding numerous close-to-death situations which characters must escape from, realism and less religious symbolism, and arguably most importantly; the Hammer films focus on heightening Frankenstein’s brutality (Picart, 24).

Versions of Frankenstein by Hammer Film Industry focused more on the brutality and realistic inhumanity of both Victor Frankenstein and his monster, highlighted by shots of Victor Frankenstein operating on and assembling his creation with clever camera positions that allowed the film in and of itself to not be incredibly gory, but to still show everything through the sounds of saws cutting bones, and facial expressions without showing the actual operation (Picart, 25). In later movies, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, directed by Branagh in 1994, these themes of brutality and confident sexuality, along with gender, are enhanced (Picart, 26). These themes become apparent in the notable scene where the Wretch kills Elizabeth on Victor’s and her wedding night; except the Wretch kills Elizabeth not by strangulation like in the novel, but by reaching into her chest and pulling out a still beating heart in front of Victor (Figure 6). The violence of this scene marks a notable change in the brutality of Frankenstein’s creature and his larger separation from being fully subservient, and sometimes more child-like and even weaker, being that is visible in movies like Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman.

The roles of the women as lovers and feminine domestic shadows is also increased as Elizabeth’s death causes Victor to fulfill his main promise to his creation, in creating a feminine monster to serve as a wife for the Wretch, something drastically different from Shelley’s version.. In doing so, he combines both Justine’s and Elizabeth’s bodies and resurrects her, yet when the resurrection leads to both Victor Frankenstein and the Wretch fighting over who is now the ideal bride for both of them; with a monster just a monstrous as the Wretch, fulfilling his wishes and Victor’s betrothed, Elizabeth-Justine plays into the feminine and monstrous shadow role by burning herself alive (Picart, 32). The female monstrous shadow, as defined by Kay S. Picart, are the feminine monsters who don’t get to choose their fate and either escape through suicide, or through a masculine character’s choices, something that this new resurrection of Elizabeth and Justine portrays. By the mid to late twentieth century, Frankenstein as a character had been solidified in blaxploitation horror films as the image of people of color for an intended audience of colored people, and had also solidified the character of Frankenstein as solely masculine, without any of the slight ambiguity present in Shelley’s text (Heffernan). Branagh’s production draws more from the 1818 edition of Frankenstein where the parental role of Victor Frankenstein is highlighted and likens the fear and disgust of the Wretch to that of a revulsion to life, especially abnormal life where one is born twice; once when he first wakes on the table and later once Victor has killed him in fright and hatred (Branagh).

The roles and standing of characters also drastically change throughout time and through different film productions. As the Universal Frankenstein franchise continues, Frankenstein as a character gains the ability to seem more human, he starts as a child who cannot speak and as the films continue, gains the ability to speak, loses that ability, then gains another brain and can speak again (Picart, 30). In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, characters shoot around rapidly in standing with each other; Henry Clervel becomes inferior to Victor Frankenstein while Elizabeth becomes his emotional equal, if not superior, and gains the ability to choose not to marry him (Picart, 32). Justine as a character, for the most part, disappeared in film and was never a particularly notable character, until Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein placed her back in a spotlight. In the Hammer films and movies such as Frankenstein: The True Story or Frankenstein Created Women, Elizabeth is portrayed as an arrogant character comparable to Victor Frankenstein and loses the gentle character she has in Shelley’s novels.

In the modern-day portrayal of the Wretch, while the purposes and influences behind changes in the Wretch have become less relevant, the changes themselves haven’t disappeared, Despite the fact that stage performances and minstrel shows with the Wretch have disappeared, the aspects of his character taken from the caricatures of Caliban and black slaves still remain in his appearance, lack of ability to speak, and behavior. The green-gray skin color from Karloff has remained present, though has shifted more to a bright green. Polio has become less of a source of social hysteria everywhere and unethical practices and experimentation to deal with polio have become stories of the past that are often glossed over, yet the Wretch’s character still holds the remnants and influence of the hysteria around polio in his character’s gait, musculature, and respiratory system. The changes in the roles of characters to better portray social views of women as lesser and more likely to be killed and to highlight the monstrosity, strength, and even masculinity in the Wretch have also been ingrained in the character, despite these new characteristics not being present in Shelley’s writing. Throughout the two centuries since Mary Shelley originally wrote and published Frankenstein, the character of the Wretch has changed from a creation superior to man in all but appearance to a commonplace symbol of Halloween and horror. These changes have occurred through, and been catalyzed by, the usage of the Wretch as a racial caricature, propaganda, a representation of the hysteria around; and the dangers of, polio and as a way to show the gender roles in society.

Bibliography:

Duyfhuizen, Bernard. “Periphrastic Naming in Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein.’”

‘FRANKENSTEIN.’” Studies in the Novel, vol. 27, no. 4, 1995, pp. 477–92. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/29533087. Accessed 3 Mar. 2023.

Brough, Robert and Brough, William. “Frankenstein; or, the Modern Man.”Adelphi Theatre,, Jan

12, https://www.umass.edu/AdelphiTheatreCalendar/img018f.htm, Accessed 13 Feb 2023.

Canfield, Kevin. “James Whale: A New World of Gods and Monsters.” Film Quarterly, vol. 58,

- 4, 2005, pp. 64–65. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2005.58.4.64. Accessed 28 Feb. 2023.

Codr, Dwight. “Arresting Monstrosity: Polio, ‘Frankenstein’, and the Horror Film.” PMLA, vol.

129, no. 2, 2014, pp. 171–87. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24769446. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

Heffernan, James A. W. “Looking at the Monster: ‘Frankenstein’ and Film.” Critical

Inquiry, vol. 24, no. 1, 1997, pp. 133–58. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344161. Accessed 13 Feb. 2023.

Malchow, H. L. “Frankenstein’s Monster and Images of Race in Nineteenth-Century

Britain.” Past & Present, no. 139, 1993, pp. 90–130. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/651092. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

Peake, Richard Brinsley. “Frankenstein. A Romantic Play in Three Acts.” Dick Standard Plays,

Accessed 13 Feb 2023.

Picart, Caroline Joan (“Kay”) S. “Visualizing the Monstrous in Frankenstein Films.” Pacific

Coast Philology, vol. 35, no. 1, 2000, pp. 17–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3252064. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus. Longman, 1998.

Shelley, Mary, Selected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly, letter 1,378. Baltimore, Johns

Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Walker, Malea . “The Evolution of Frankenstein in Comics and Culture: Monster, Villain, and

Hero.” Library of Congress, https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2018/10/evolution-of-frankenstein-in-comics-and-culture/. Accessed 10 Feb. 2023.